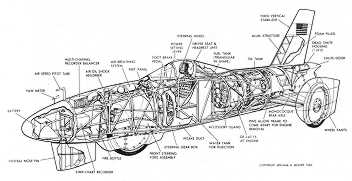

Wind-tunnel testing proved a three-wheeled design was aero-dynamically best for the speeds Craig was attempting

The jet car program was getting to the stage where I needed wind tunnel tests to prove the aerodynamic qualities of the design. The only practical and logical time to run the tests was, naturally, before the car was built, and it would have to be done with a specially-designed model. After the tests, we could easily make the necessary modifications to the design and,when the design was perfected, we could build the car exactly like the model.

Certainly the most important consideration in building any race car, particularly one in which you expect to go over 400 miles an hour, is its aerodynamic design--the main factor that makes a jet car different from an airplane. If it's designed improperly and doesn't have the necessary amount of negative lift, the car will fly. That wasn't exactly what we had in mind for going fast. The fact that this had happened to a number of land speed record attempt cars at the Salt Flats was constantly on my mind. Aerodynamics also plays another highly important role in the design of a race car. Proper aerodynamic design allows a car to go fast. That we did have in mind.

Art Russell and I had talked about a wind tunnel model while we were building the first one; so he wasn't at all surprised when I showed up at his house one evening with the first model and a stack of drawings. "What took you so long?" he asked.

However, to help guide us in making the model, we decided that before we started we should talk with someone who had wind tunnel knowledge. So it was back to the air guard, and once again they came through. Mike Freebairn contacted a fellow named Rod Scbapel, who worked for Task Corporation. Rod had all of the qualifications. He was an aerodynamic engineer with vast experience in wind tunnel testing and a former racing enthusiast.

Rod was really interested in the model. He must have been because when I told him I didn't have any money to pay for the tests, he didn't throw me out of his office. He said that Task certainly couldn't test the car for nothing, but there might still be a way. He told us that if we built our own model the fellows at the Naval Post-graduate School in Monterey might do the testing for pretty close to nothing. They had been known to do a little moonlighting on weekends, and for a few dollars an hour he thought they might be persuaded to run a test on the model.

Rod made some suggestions and changes in my plans, and furnished Art and me with a new set of drawings with which to build the second model. We spent a lot of time on this one. It had three different nose configurations and two different sets of rear fenders that were removable. This way we could run it with or without the fenders--to determine the air drag of the exposed wheels--or with any of the three different noses. We had started to get pretty sophisticated.

Bill Moore, meanwhile, was working on more art work for a flip chart presentation that I hoped would get me some sponsors. Someplace along the line it would be nice if we came up with some money. I had sold about everything I owned and had taken a part-time job at a garage in Santa Monica just to get the money I needed for the fellows to do the wind tunnel testing. Lee was still working at the drive-in, but it took most of her salary just to feed us--us and the gang of people who were in and out constantly. It was like running a sandwich shop--there were a lot of people helping.

We spent three weekends in Monterey and came away with outstanding data on the aerodynamics of the car. We even had photographs, and everything looked encouraging. The tunnel test had proved the three-wheel configuration was the perfect design for the speeds we had in mind. I was ecstatic--broke, but ecstatic.

The next step was to name the car. We couldn't just keep calling it "jet car" or "it." The program was beginning to take shape and a name was important. Finding one didn't take long. I had always been patriotic, and I wanted a name that was worthy of the car that would bring the world's land speed record back to the United States. I had built a model of Charles Lindberg's plane, "The Spirit of St. Louis," when I was a kid and for some unknown reason this popped right into my head. Then it hit me--the perfect combination of patriotism and adventure--The Spirit of America!

The name probably didn't impress Mr. Tuchen as much as it did me, because things at the house were getting more and more hectic by the moment. Here was the plot: Walt Sheehan had finalized the drawings of the air inlets. I had contacted a pattern maker by the name of Frank Fellows, to help me with building the molds for these huge inlet ducts. Walt and Frank were coming over every night, along with another friend, Henry Brown, who worked for H. I. Thompson Fiber Glass. Henry was invaluable with the fiber glass engineering and lay up. This was a complicated process that entailed laying weaves of cloth in with the fiber glass. It had to be done properly or the ducts would not have the necessary strength.

Ted Thal of Thalco, one of the foremost fiber glass industry pioneers, had given me the glass and resin--components used in our fiber glass construction.

This frantic activity was going on in the living room. The plaster cores that Frank and I had made (around which the fiber glass ducts were to be formed) were about ten feet long and were works of art. They were hand-finished and lacquered to the configuration of the inside of the ducts. The procedure used in building them was complicated. After they were built, it was necessary to putty, sand, block, and lacquer them--they had to be just perfect. Then we had to lay fiber glass over the molds. When they were all done, we had huge ducts that weighed about 300 pounds each.

We had sprayed a parting agent over them before we laid the fiber glass, but after we broke the cores out, there were still tiny chunks of plaster that stuck inside the ducts. This is where Lee came in. She was the only one small enough to crawl into the ducts and chip the little pieces out; so we would dress her in flannel pajamas and slide her down into the ducts with a hammer, chisel, and flashlight. She would stay in there for hours and was perfectly content with her chore--except when someone left the screen door open and our dachshund, Spirit, got in. The first time it happened, we heard Lee screaming and rushed in to find her stuck half in and half out of the Mold, with Spirit sitting there licking the bottoms of her feet. After that it was a pretty routine thing. Lee would scream and one of us would matter-of-factly go in, pick up the dog, and put him out. He finally quit doing it because there was so much noise and activity outside that he was afraid to run the risk of being put out.

The whole inlet duct operation was very important. The ducts had to be perfect, their insides as smooth as glass. Building ducts that won't collapse for a jet engine is difficult because of the tremendous pressure that builds up as the jet engine gulps fantastic quantities of air. Dr. Ostich had run only once on the Flats with his jet car and had failed to do well because the ducts collapsed at only 60 percent power. Even the aircraft industry had its problems from time to time with this situation. They would get a plane completely designed, build a mock-up, and find that the inlet ducts just wouldn't stand the stress. In addition to this, no one, including the aircraft industry, had ever built a set of fiber glass ducts; so this was somewhat of a pioneering effort.

Anyway, we had the special weaves of cloth, all going in certain directions--twice as thick in the corners--and all feathered out. Man, it was intricate. The engineering and construction had to be perfect. Fortunately I had a design engineer, an experienced pattern maker, and a fiber glass expert to help me--not to mention Lee and Spirit.

All of this stuff and all of these people were arriving constantly. It was amazing. Bill and Art were working on the model in the dining room, which was also the drafting room. They were painting it and lettering the name on it. Everything was going together somehow with nothing--piece by piece and part by part. But it was going together amidst the most awful confusion I had ever seen.

|

| The jet car leaves the garage for its trip to the body shop. |

On the day another truck load of supplies (this time it was some free tubing from a friend at the Tube Distributors in Los Angeles) and Mr. Tuchen arrived simultaneously--as a matter of fact, the truck almost ran over him--I realized the project had gotten out of hand. There were parts all over the backyard, air inlet ducts in the living room, a half-built trailer in the driveway--a 40-foot Fruehauf van that I had borrowed from Ed--and a garage crammed full of material. Well, it was incredible. It was definitely out of hand, and if we didn't get a sponsor soon, the whole project would be down the drain--it would take not only me with it, but also a lot of my friends who had worked hard on the Spirit.

Art, Bill, and I quit everything else we were doing and put the finishing touches on the presentation. From that point on, it was Operation: Sponsor. It had to be. There was no money left and no more friends to give us supplies.

When we finished, the presentation was impressive. The flip chart was a masterpiece because Bill had done many for Hughes Aircraft and he knew what he was doing. And the model--it was gorgeous! We built a beautiful case for it, which made it look even more impressive. It was February 1, 1961, and I was ready.

Andy Anderson's Shell Station, on the corner of Sepulveda and Venice boulevards, was an old hangout of mine. It was right across the street from the Clock Drive-in of my high school days. It was also the same corner where I used to wait for the people to pick me up to go to art class; so, one way or another, I had hung around there for years, and Andy and I had become good friends.

I had bought a '39 Ford pick-up for $150 and had painted it silver-frost blue. It had mahogany sideboards and was beautifully lettered "Craig Breedlove, Spirit of America, World's Land Speed Record Attempt." My business cards said the same thing. Now that I look back at it, that truck was pretty neat, and I had done a lot of restoring on it while waiting for one thing or another for the Spirit. It had rolled and tucked upholstery and a dark blue metallic grill and a fairly strong engine--the whole bit.

My attire wasn't quite as splendid because I didn't even own a suit. When I left home, I had three pairs of levis, a whole bunch of T-shirts with writing all over them, and one, that's right, one, sport shirt. So, I put on one of the clean pairs of levis and the sport shirt and polished up a pair of shoes that I had gotten for high school graduation. In fact, I only had one decent pair. The rest had been ruined in the garage.

Andy came out to talk with me as I parked the truck at the back of the station. "Who's in charge of the Shell district office next door, Andy?" I asked him. He told me a man named Bill Lawler was the district manager. I wrote the name down on one of my cards.

The receptionist at the Shell office looked a little surprised when I struggled through the door with the model case and flip charts. I told her my name was Breedlove and handed her my card. "I want to see Mr. Lawler, please," I said. With no appointment or anything, there I stood in all my splendor.

She opened the door to his office and said, "Mr. Lawler, there's a Mr. Breedlove to see you, " and I heard this big, deep voice say, "Send him right in." The place shook a little bit and I thought, "Oh, boy, fasten your seat belt."

I trotted through the door with my "dog and pony show." He looked up in amazement and said, "You're not Victor Breedlove." I later learned that Mr. Lawler had a Shell dealer named Victor Breedlove, whom he had been expecting.

I took a deep breath and blurted out--in one sentence, I think--"No, sir, Mr. Lawler, I'm Craig Breedlove and I'm here to talk to you about a project that, I think, will not only benefit myself but Shell Oil Company as well, and I'm sure it will interest you because I am going to bring the world's land speed record back to the United States after an absence of 34 years, and after many people have tried and failed, and I have the car that can do it."

He looked up in bewilderment, took off his glasses, and said, "You've got ten minutes."

The flip chart presentation ran as smooth as silk. I had it down pat, and it was soon apparent to him that it was not only feasible, this wild and woolly scheme of mine, but it was a public relations gem. After an hour of charts and photos and wind tunnel test results, Mr. Lawler was on the edge of his chair.

The box with the model was in clear sight, but I hadn't said a word about it at this stage. Mr. Lawler kept looking at it and finally, when I paused at the end of the presentation, he could stand it no longer. "All right, what's in the box?" he bellowed.

I reached down and opened the mysterious box and all you could see was velvet lining and a piece of purple velvet covering an object. "Mr. Lawler," I said as I whisked the cloth off the gorgeous, absolutely beautiful model, "this is the Spirit of America."

Well, he just came straight up out of his chair and grabbed the thing out of my bands and disappeared through the door. I thought he had flipped. I could hear him running down the hall shouting, "Look at this! Look at this!"

Finally he came back and panted, "How long has it been since you've bad a decent meal?"

I was truthful when I answered, "Quite a while."

"Well," he said, "I'm taking you to lunch."

At lunch he asked me if I really thought I was going to break the world's land speed record. "I don't think I'm going to break the record, Mr. Lawler; I know I'm going to break it," I answered him. We both knew I meant it.

He looked at me square in the eyes and said, "Craig, I know you are, too, and I'm going to do everything within my power to see that Shell Oil Company helps you do it."

Shell, like many giant corporations, is a conservative company, and the fact that I had sold a district manager on the project didn't mean that the company was sold. I had one tremendous advantage, however. Bill Lawler was a persistent man, and this project became almost as important to him as it did to me--and he was a super-salesman. As a matter of fact, he is now a vice-president of Shell; so he was no ordinary district manager.

|

| Getting the 11.5 foot wide car out of the garage and down the driveway presented obstacles: the fence, the porch, and Mr. Tuchen's hedge. |

The next step, Bill Lawler said, was to muster enough force on the West Coast to interest the big wigs back in New York; otherwise they wouldn't even bother coming out to talk about it. "Do you have a suit?" he asked. I told him I didn't but that I would get one somehow if he thought I needed one.

"Well, you need one, and you need it Monday. That's the day we're going to sell Al Hines," he said. Al Hines was a division manager and a close personal friend of Sid Golden, Shell's vice-president in charge of marketing.

I went down to Jim Clinton Clothes and for $35 bought a suit, tie, and dress shirt. It was high school graduation all over again, except this time I hoped I was graduating from the ranks of the starving.

Well, we sold Al Hines and then a vice-president from San Francisco. It was all part of Bill's strategy to entice Sid Golden to the West Coast to see the plans. The three of them wrote to him, but he said flatly, "No, we're not sponsoring some crazy kid and his wingless airplane and that's it."

That answer would have been enough for most people, but not Bill Lawler. He wrote right back and said, "Listen, you can't turn this thing down without even seeing it."

I guess his persistence got through because Sid Golden wrote back and told him that he was going to be on the Coast the next week to see his son off to the Marine Corps and he would talk to them about it.

When Golden arrived, Bill and Al met him at the bar of his hotel. They let him get about three martinis under his belt before they really started to work on him. "All right, all right, I'll look at this jet or whatever it is."

The meeting was set for the next afternoon. I spent most of the night working on the presentation and perfecting the unveiling of the model. When I arrived at the Shell office, Bill came out and said, "I hope you've got your selling cap on, kid, because this guy's tough. Besides, there were a lot of martinis last night and, well, he's not feeling too good." I almost dropped the model case.

The presentation went even better than it had the first time. At the very end I proudly thrust the model in his hands and said, "Mr. Golden, can you imagine one of these models in every home in the United States with a Shell emblem on it?"

He just looked at it and said, "Yes, I can. You've got something. I'm going to okay this project on one condition--that our engineering group investigate it and give us a positive okay that it's sound in engineering and design, and we're not getting into anything that someone's going to get killed in."

I knew I had made it because I knew that the car was sound in every aspect. I was especially gentle with the model as I put it back into the case because I knew that a new age of racing had been born and this was its first child. As soon as the Shell engineers approved the project, I went straight to the telephone. I knew Shell's decision would give me leverage with Goodyear. I called Walt Devinney, the racing tire engineer who had been to see me earlier, and said, "Walt, I have Shell Oil Company as a sponsor for the jet car. Can you see if the picture has changed any there?"

Devinney was a little Stunned, but he finally said, "You really have Shell? You mean Shell Oil in New York?"

"That's the one," I told him.

"Let me do some checking, Craig, and I'll call you right back," he said.

Shell was about a $30-million-a-year customer of Goodyear. Bill Lawler bad told me that certainly Goodyear would now be a lot more willing to consider my project.

Walt called back and said, "Can you come to Akron, Craig, to talk with some of our people?"

I was on a plane next morning, and when I got there I learned that the "some of our people" were Russell DeYoung, president; Vic Holt, executive vice- resident; Mike Miles, vice-president in charge of sales; Bob Lane, director of public relations; Tony Webner, director of racing; and Walt Devinney. It was quite an impressive group for a 23-year-old hot-rodder, but I had the presentation polished to a fine hue, and I had Shell behind me. There would be no more of this David and Goliath action for me--I already had one giant under my belt

Well, when I got in that board room and looked at the long table and the important-looking surroundings and the important-looking people, I was shakier than David had ever been. I prayed that my slingshot would hold out.

After the presentation, Vic Holt said, "Craig, I guess what you want to know now is whether Goodyear will build tires and help you financially, is that right?"

"That's right, Mr. Holt. I'm very interested in that," I said meekly.

Holt asked Walt to take me down and show me around some of the tire-making operations while they discussed the matter. We left the room, took an elevator down to the main floor, and walked back into the plant. I didn't have too much to say because, well, I guess, because my heart was in my mouth. Fortunately, we didn't have too long to wait. Walt got a phone call in the plant, and when he came back, he looked at me and said, "You've got it, Craig. They said yes."

I leaned against a pillar and the realization hit me--the realization of what I had put together. It all had to be ready by summer. Mr. Tuchen was right. It really wasn't a hobby; now it was a business.